Deceptions in Mineral Resource Reporting & Prevention

Making decisions about the purchase or sale of licenses or projects is difficult, as the quantity of underground resources is open to interpretation, and there are many technical details that very few people can master. This situation, which is a weak spot for investors and managers, often exposes mining investments to fraud. In this article, we primarily discuss the deceptions in reporting and the precautions that can be taken against them.

The existence of documents passed around under the terms “JORC report, NI 43-101 report, UMREK report, etc.” does not guarantee that positive results will be obtained from the relevant projects.

1. Introduction

Whether you’re starting anew or managing a large mining portfolio with ongoing projects, it’s important to remember that you must proceed by setting a strategy that aligns with your capital and goals and fulfilling the requirements to maintain it. Losing focus can expose your company to all kinds of fraud.

A number of professionals, including mining, geology, processing, environmental, and civil engineers, as well as sociologists and lawyers, can sign off on the relevant sections of these reports, by having accredited their competence with reputable institutions.

Anyone can do modeling or write a report, but for these reports to be acceptable, they must be signed by approved individuals at certain standards. Even if you do not plan to present your reporting data to institutions, stakeholders or the public, ensuring that your work is technically compliant with these standards will benefit your company in every aspect.

Reviewing the **Rational Investment Strategy in Mining** can be inspiring for a solid foundation regarding mining investments.

What is the meaning of “report” in mining?

In mining, reports are written documents, statements or announcements published in various media that convey the results of research, examination, or modeling on topics where information needs to be communicated. Reporting can be a periodic publication intended to inform the public, or it could be a specific technical review published as a booklet and served only to a particular audience.

Mining exploration and operational projects are products of company strategies on a regional scale. The identification of mineral resources and the confidentiality of information about this discovery are company policies. The company may share the desired report under a confidentiality agreement and may close certain subject headings to public release if necessary.

You should first clarify why you need modeling, reporting, or reports.

2. Basically Non-Compliance with Reporting Standards and/or Competent Person Definition

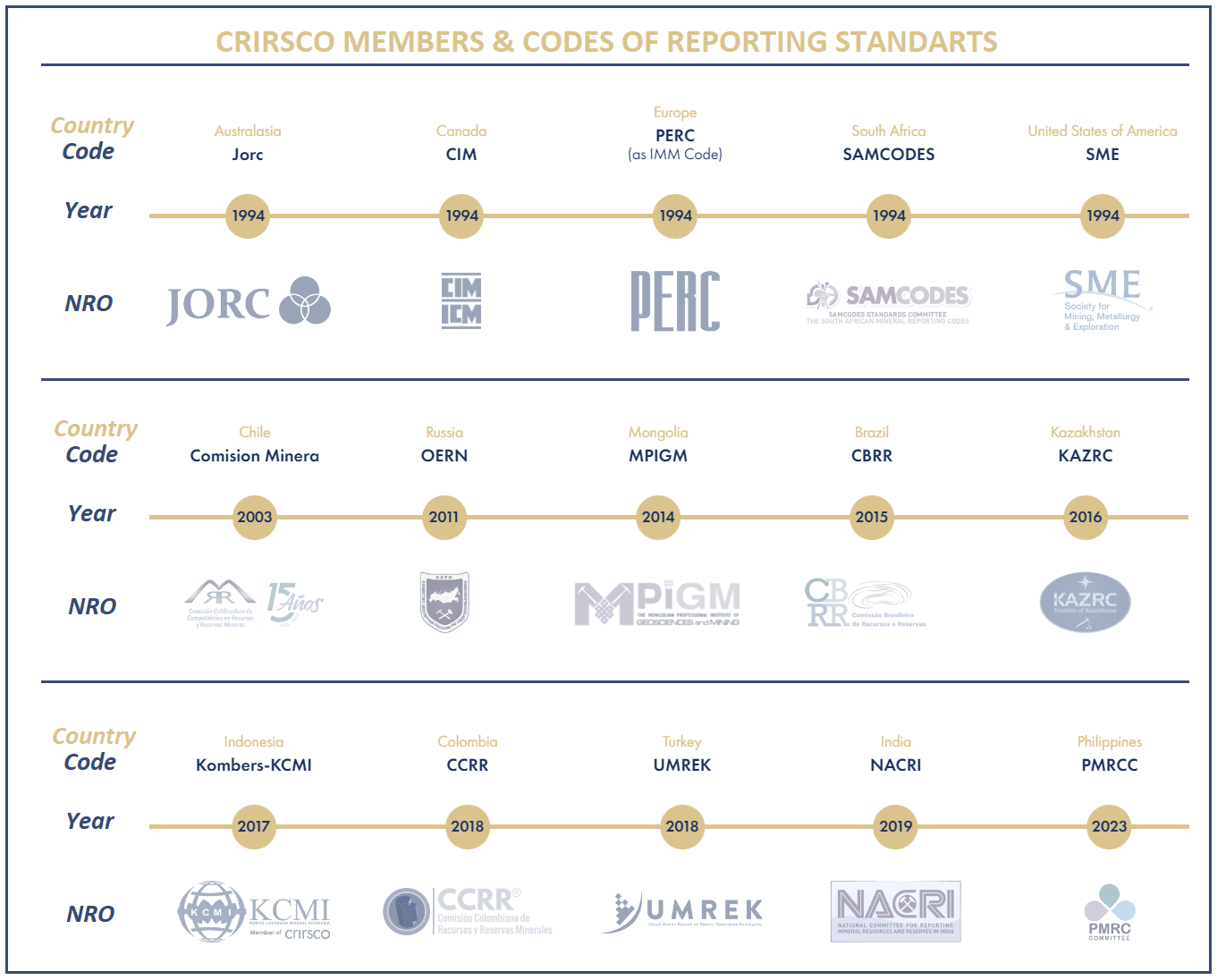

Nations, under the umbrella of CRIRSCO, publish their own reporting codes/standards (NRO Codes) with institutions delegated to use specific templates and approve the professionals who will present these reports or data. Reports that are stated to comply with these codes provide assurance in the presentation of publications on mining resources. Although efforts are made to control this under the principles of transparency, materiality, and competence, only ethical values can protect the technically exploitable reporting.

2.1. Confirmation that reporting is done in standards/codes that the institution to which it will be presented can respect.

Prevention: Determine at the outset whether the institution to which you will present the report or data will accept the code in which the report is written in compliance (Example: JORC-compliant report). You can confirm the current version of the codes named by the national reporting organizations (NROs) under the CRIRSCO umbrella, which are generally accepted, on the CRIRSCO website or on the code’s own website.

In the given photo, you can find the reporting organization under the CRIRSCO umbrella, the relevant countries and the code / standard name that can be accepted by the institutions.

2.2. The professional who will present the report, sign off as a Competent Person (Qualified Person, etc.) and consent does not have competence in the relevant subject.

Prevention: The professional who will conduct the reporting or documentation, manage a certain study and present the data must provide the competence defined in the code in which the reporting is made in compliance. The “consent form” of the professional whose signature will be on the authorized person approval page in the report must be examined and the competence must be confirmed and, if possible, the activity must be verified with the member name or number from the member list / website of the institution (RPOs, in ex. AusIMM) of which he/she is a member.

Sample profile of a competent person: Experienced for a certain period (at least 5 or 7 years) in the subject of reporting (resource estimation, presentation of exploration data, etc.) and mineralization style, and in addition, it is mandatory to be an active member of a reputable organization (RPO) that has the authority to “exclude from membership and subject to sanction” recognized by the relevant code. The institution that has ethical principles and is a member usually requests a professional resume and at least 2 members as sponsors. Each code may have a different “Competent Person” definition, it would be useful to review the current version of the relevant codes on the NRO websites (click for JORC description of Competent Person).

2.3. Going beyond the reporting subject.

Prevention: The main subject of the report to be presented to investors, the public, and other shareholders must be clearly stated and all relevant data must be provided transparently. “Exploration targets, exploration results, mineral resources, ore reserves or results of technical studies” are frequently used subjects, but are not limited to these, and should not be exceeded by taking competence into account in the subject headings on which the report is written.

3. Manipulation of Resource Tonnage (Volume) and Grade Obtained from the Model

The most common method of deception is exaggeration made on solid models and block models to be used in mineral resource and reserve estimates. Exaggerating the productivity and potential of the mining site, and therefore the estimated income that can be obtained, will create interest in investors and managers who examine this data and cause them to be deceived.

All criteria under this heading are quite critical and for this, please note that the digital “3D model” from which the resource data for the project you will be evaluating is obtained must be taken for examination.

For details on this subject, it would be useful to review our Basic Concepts of Resource Modeling article and video.

Also, The effect of density values on tonnage, mentioned in Article 5.3, can be included in this field.

3.1. Inconsistencies detected as grade accumulations or sudden increases/decreases that are well above expectations in the resource/reserve model from which the resource data will be obtained.

Prevention: Verification of the regular use of sufficient quantities, appropriate standard intervals and appropriate frequency of sampling on the mass and quality assurance / quality control (QA/QC) samples, examination of the core mill process flow, taking witness samples from the drillhole cores and the field in person and sending them for analysis in internationally accredited laboratories. Checking whether standard division intervals are adhered to in drilling or sampling logs.

3.2. Adding “unreasonable” extra points on or outside the drillhole traces, playing with ore directions and slopes, combining parallel/extended secondary ore bodies as if their spaces were filled, thus inflating the solid model (wireframe).

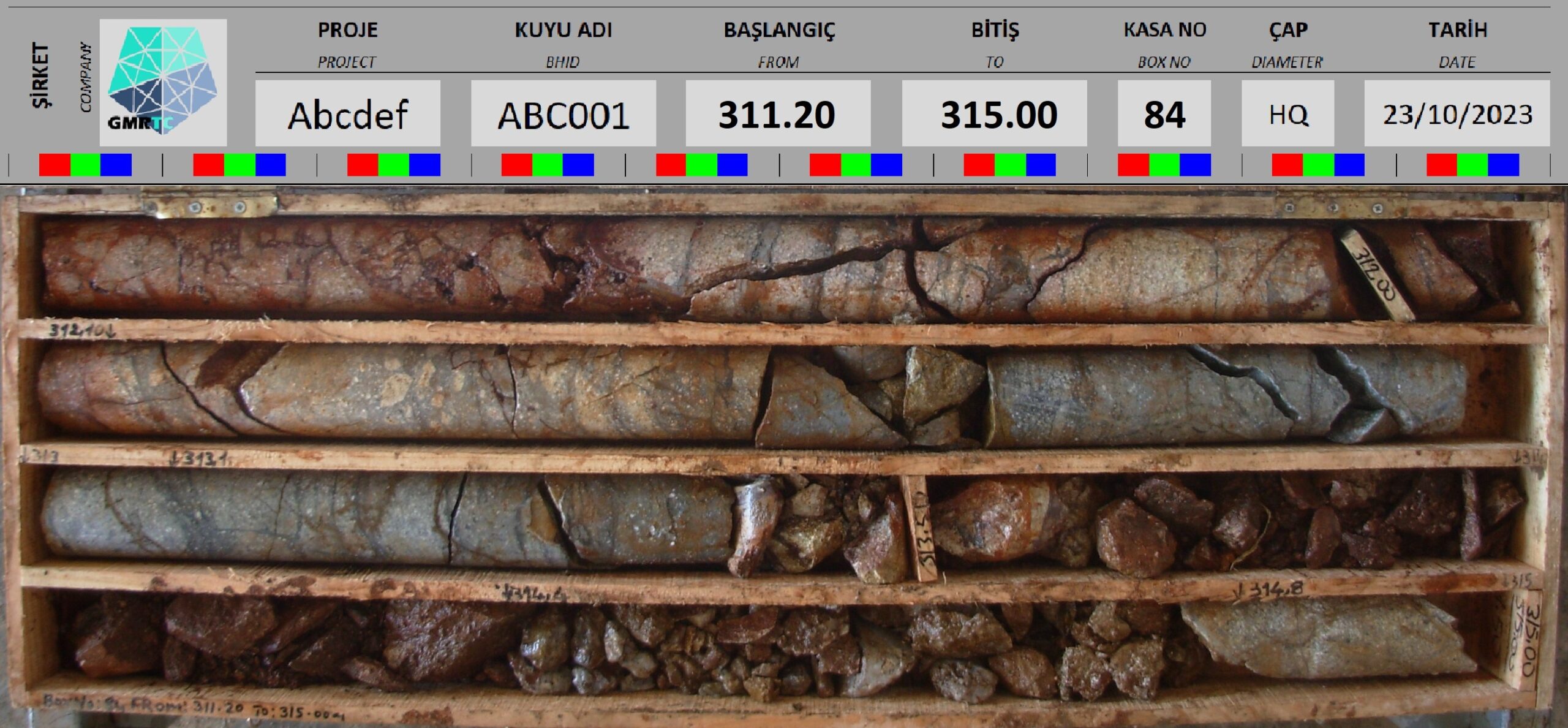

Prevention: Examining the drillhole logs and sampling data, core photographs by an experienced resource geologist, and making observations in the field, coreyard, core shack if possible.

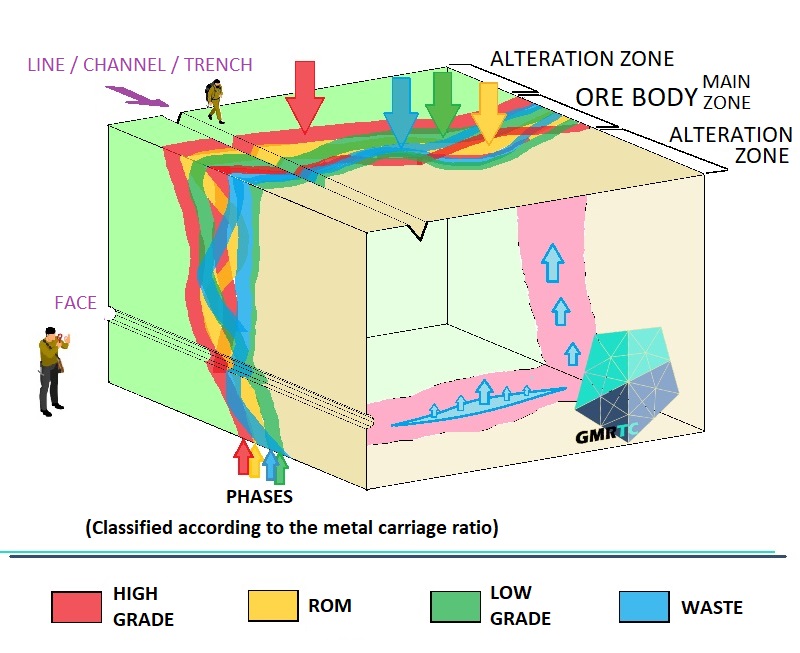

3.3. Increasing the average grade by including the low-grade, large volume zones with wide continuity cut by the drillholes and the very high-grade narrow volumes in the same solid model and performing the grade estimation together in the block model.

Prevention: If possible, by examining the mineralization coreboxes in coreyard or core shack, field studies, and grade control samples, drillings and core photographs during the mine operation, to distinguish low grade zones, to determine the trends of very high grade (HHG) zones and to separate solid models and to make block models.

Independent of the cut-off grade to be used for the operation, the resource cut-off grade should be determined from the moment the exploration project starts to mature and the locations where the values cut below this grade are interpreted should not be included in the solid model and should not be used in the block model calculation. To give a short example, when a few meters of “ROM grade” intersected in a drillhole are included in the modeling, tens of meters of “very low grade” (vLG) cut before and after, the volume will swell and the resource will be exaggerated after the grade estimate made by evaluating them together. This situation is frequently observed especially in some types of mineralization that show clustering (Antimony (Sb), Cu, Pb, Cr, etc.).

3.4. The distance between drillholes and/or sampling exceeds the limits of joint evaluation specific to the mineralization in question or the ones obtained with low grade from the drillholes (infill or exploration) made in between are kept/removed and not included in the data to be used in creating the model used in resource calculation.

Prevention: Resource geologists should question the average distance between the points where the drillings enter the orebody (drillhole grid spacing), scan the drilling locations in the field with the help of aerial photographs and, if possible, examine the locations where drilling is expected but which are not digitally recorded in the data.

3.5. The estimation method selected for the block model and the estimation application directions do not match the mineralization dynamics.

Prevention: Experienced resource geologists should examine the entire project with drillhole cores and mineralization type, and determine the commodity distribution directions and trends according to the mineralization dynamics.

3.6. The resource/reserve classification tables in accordance with the reporting standards are not provided in an understandable manner.

Prevention: The figures related to resource classification should be confirmed by calculating them on the block model with drillhole datas. Examining the drilling network and minimum sample quantity engagement used for classification and the table with optimum distances within the network. Questioning the fact that no significant figures belonging to a class other than the one stated as “inferred” are presented.

For details on this subject, it is useful to review the Mineral Resources & Reserves Classification for Reporting.

3.7. Excessive expansion of the solid model beyond the drilled area.

Prevention: It is essential to determine the reference extension standards according to the type of mineralization. Observation in the field to examine the type of mineralization and alteration extent, examination of drillholes in a 3D digital environment with regional dynamics.

3.8. Not interrupting the gaps between faults, boudinage structures and lenses in the solid model.

Prevention: Examining outcrop observation records of exploration activities, questioning whether structural elements intersect with drillings or operations by extending them using strike/dip values. Examining drillhole logs, core photographs and, if any, operation maps in a 3D digital environment to reveal the relationship between the ore body and these structures, determining possible displacements caused by faults on the model.

According to the determined mineralization type, in order to reveal the characteristics of the ore body to be examined such as clustering, lens structure, boudinage and stratigraphic limitation, if any, on-site observations should be carried out in the operation. If there is no operation in the licensed area, on-site examination of other operations, cuts or open surfaces in the region. Making sure that the expected structural features are reflected in the model.

It is important to record outcrop observations, drilling records (drillhole logs) and core photographs obtained in exploration activities, and geological map records in open pit and underground operations in the most appropriate way. With these records, the most realistic models are obtained, and the directions in which the resource potential can expand are determined. In this regard, it will be useful to ask for support from experts who have extensive operating experience and are competent in structural geology.

You can review the following articles for the detection of faults in the field and their mapping and recording in open pit or underground.

How to Identify Faults in the Field? & Purpose of Detecting

3.9. Bonus: Resource estimation cannot be provided with 3 drillholes (or 5, even 7)…

Prevention: Examine, do not decide.

For details on this subject, it would be useful to review Solid Modeling Methods for Mineral Resources “Wireframing”.

4. Non-compliance and Manipulation in Sampling, Analysis, Measurement and Photography

Manipulations such as misleading resource and reserve estimates, superficial interpretation of metallurgical test results or taking samples from other sources for the purpose of examining environmental effects may show the real potential or exploitability parameters of the mine differently than they are.

4.1. Not providing the names and definitions of the sampling and analysis methods used.

Prevention: It is essential to know how the sampling and analysis methods are performed, contact the project or laboratory that refers to it and learn the details. Asking the liable of unnecessarily long copy-paste texts that appear in the report to clearly understand the method.

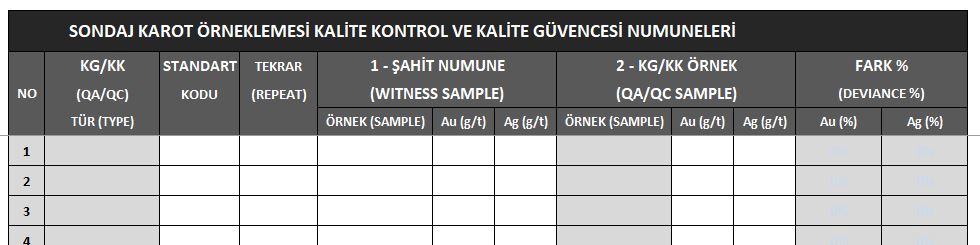

4.2. Omitting addition of quality control and quality assurance (QA/QC) samples regularly at sufficient intervals and/or not keeping their records regularly.

Prevention: Adding a certified standard sample with known value at certain periods, adding an extra sample duplicate from the same interval at certain periods, checking that a blank sample is taken at the end of each drilling sampling. Also, getting confirmation that the laboratory is progressing by duplicating the analyses at regular intervals (e.g. every 5 samples).

4.3. Samplings are not meticulously supervised by personnel who have received sufficient training and experience.

Prevention: Spending time with project personnel and managers in the field and coreyard as usual within the workflow, examining their procedures and habits, checking the suitability and cleanliness of the rooms, equipment and consumables they use for sample preparation. If possible, examining the pre- and post-sampling photographs of the channel, line, pit sampling locations or systematic soil sampling locations made in the field, obtaining detailed information from the personnel about the methods used.

Checking the personnel’s habits of using tools or equipment that will directly manipulate the analysis result by contacting the sample, especially in sensitive commodity analyses (Coreyard personnel wearing rings contaminate cores w/Au).

Making sure that the personnel is careful to obtain equal pieces by paying attention to the lithology location when cutting core samples. Comparing the samples remaining in the case after sampling with core photographs at the intervals where high-grade drilling samples are taken.

It would also be useful to review Line and Channel Sampling in Mineral Exploration Field Study.

4.4. The laboratory where the analyses are performed does not have accreditation for the analysis it has conducted on the relevant commodity or material.

Prevention: Querying the certificate obtained by the laboratory for the analysis method performed on the commodity in question from the website of the accrediting institution or confirming in writing that it is active on the date of analysis. Querying the margin of error for the relevant commodity in the analysis method corresponding to the code given by the relevant laboratory in the analysis results, observing the potential of sulfur content to affect the analysis method. If possible, examining the laboratory sample preparation area hygiene and independent audit records on-site.

4.5. Observation of unusual anomalous lithology in core cases or photographs.

Prevention: Against the possibility of ore-cut section of the drillhole is shown wider than it is, lithological and geotechnical examinations should be carried out on the witness cores in the intervals where anomalies are detected, and comparing data other than the target commodity (elements) in the consecutive analysis results.

Making sure that the cores in the cases/boxes are cleaned and photographed after removing the drilling mud, and are photographed clearly under standard color and light.

5. Insufficient Transparency in Data Presented for Feasibility and Cost Analysis

When exploration activities reach a certain maturity, technical feasibility analysis is performed and the selection of operation and ore processing methods is made. After this stage, the publication of all parameters required for underground and open pit plans (LoM, LoMP) to be made is open to abuse, and failure to share information transparently, even if negative, is also a defect. In technical reports, the topics covered after this step will mostly be for the operation project and subsequent stages.

5.1. Ownership, shareholding, capital and operation are not as stated.

Prevention: Verification of exploration and operation licenses, site ownerships, and permits, if any, through relevant institutions. In the case of an operation, inspection of open pit/underground and, if possible, ore preparation activities, stockpiles and all committed units on site, examination of the licenses of the machinery fleet for later stages.

5.2. Metallurgical sampling of the mineralization has not been performed in order to reveal the critical chemical properties of the process (oxide, sulfide, clayey, etc.).

Prevention: Geologists should compare the sample locations / drillholes taken with the model and, if possible, examine the stockpiled pilot production and take samples for ore microscopy. Process engineers should select metallurgical samples from drill cores or from the field with geometallurgists and send them to laboratories for the required tests.

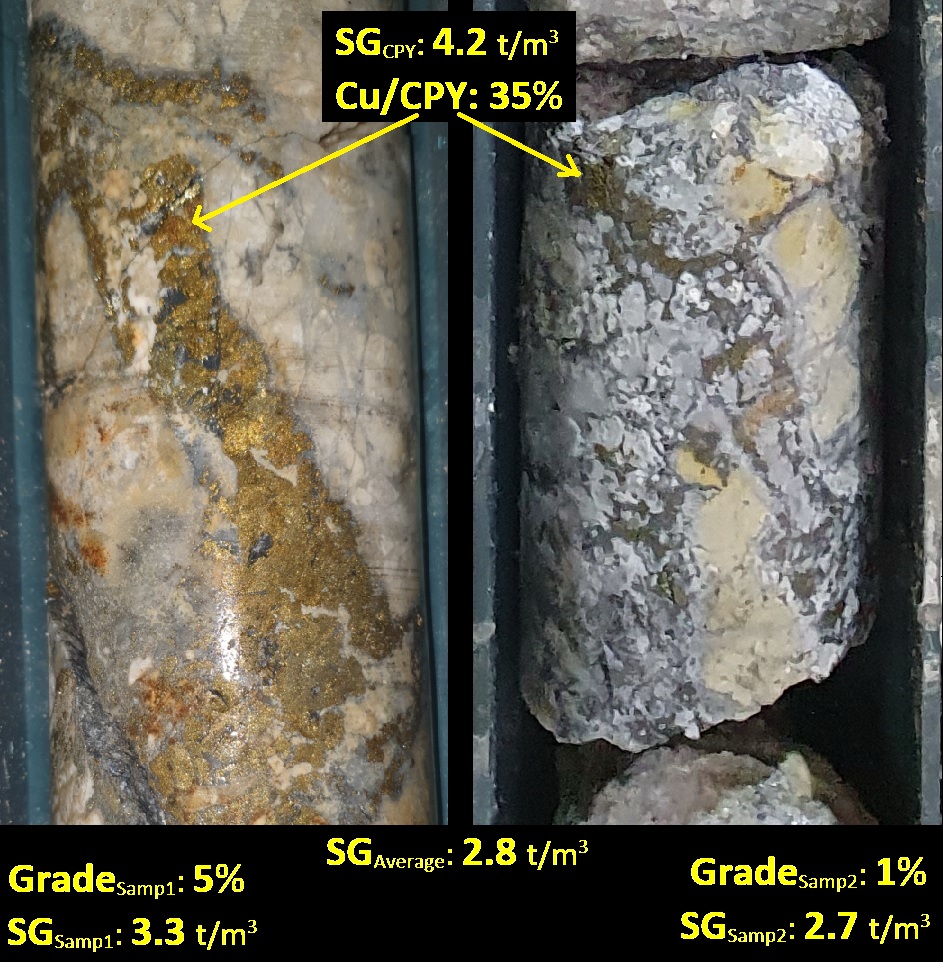

5.3. Detection of manipulation in in-situ density (SG) and bulk density values.

Prevention: Questioning the density values used to convert the resource amount obtained as “volume” from the model to tonnage or the density value determination method to be used for calculating the run-of-mine ore in the stockpile. Observation on-site that the correct method is meticulously applied, examination of the meter intervals and photographic records of the drill samples used, and, if possible, repeating the tests on witness samples.

It would be useful to review, Resource Model & Production Grade Discrepancy Investigationt: “SG” Density Determination.

5.4. Inadequate provision of geotechnical and geological studies in terms of operating method.

Prevention: Review of geological and geotechnical studies supported by important faults and alteration maps in the project area. Ensure that special studies are provided in detail for sectors separately for topics that will directly affect the cost, such as open pit slope angle design calculations or underground drift support fortification and stope designs.

Ensure that the ratios of unwanted minerals such as clay or base metal sulfides that are likely to be extracted with the ore in the area where the pit plan is possible are given clearly and explicitly. Verify that the ground survey report is clearly mentioned in areas where large masses such as waste piles, stockpiles, leach pads, tailings or dams are planned to be placed.

For technical details:

Risks & Dangers Faults Cause in Open Pits & Surface Piles

5.5. Obstructing independent audits or obscuring/changing evidence of negative elements.

Prevention: Addressing even the slightest suspicious situation detected during project audits, either on-site or digitally. Stating that temporary solutions applied in the past for different issues but not specified in the reports should be replaced with permanent ones for the sake of the project progress. Not engaging in polemics with project managers at any stage.

5.6. Not explicitly stating logistics, transportation, construction, infrastructure and seasonal impossibilities.

Prevention: Examining all seasonal and administrative dynamics of the project site on an annual basis. Questioning the suitability of climatic conditions such as plateaus, rain, etc. for work, as well as the continuity of infrastructure support commitments such as electricity, water, and connections of the relevant administrative authority during the year. Evaluating the status of the water supply required for drilling, especially in dry seasons, and the elevation of the project site during the exploration project phase. Obtaining basic information about the effects of project structures on the cost by consulting with construction or facility project engineers and considering the needs.

5.7. If there is an operating project, unit costs and performance statistics are not given in a table.

Prevention: Requesting all expenses per ton such as extraction cost, process cost, royalty, general management expenses, etc. in addition to all relevant medium-term exchange rates and commodity price acceptances used in calculations in a table. If possible, requesting production, cost and profit tables for the years in the project history.

5.8. Not providing information on the exploration or operating project history.

Prevention: Especially if there is an old/ancient operation, digital mapping of all underground openings by the survey team asap., examining the production map/offsets on-site and determining whether it has been depleted from the resource/reserve model. In addition, questioning whether any binding transactions such as excavation, construction, drilling have been carried out in the unauthorized area or adjacent license with the survey personnel on-site (open pit, underground, facility and exploration area).

6. Insufficient Clarity in Stating Environmental and Social Factors

Mining, which directly brings together the needs of nature and people, is inevitably subject to restrictions by law and socially. As a result of the dynamics specific to each region and the different decisions of administrative authorities, we can say that unfortunately, licenses and project areas are not subject to standard decisions. Many elements that can usually be put forward by local people, institutions and professionals but are not stated with sincere explanations in the reporting appear under this heading.

6.1. No statement indicating that the “positive” report of administrative permits, work permits (GSM) and environmental impact assessment (EIA) poses a problem for the region in general or the subject is not mentioned in the report.

Prevention: Investigating past examples of the perspective of legal and political authorities on mining regionally, contacting local environmental and/or legal consultants and getting their opinions.

6.2. Not stating special situations that may be relevant for sites, nature conservation areas, dam basins or rehabilitation.

Prevention: Digitally checking the borders considering the license area and mineralization orientation. If required by the geochemistry of the mineralization, conducting or confirming hydrogeological studies and acid rock drainage tests. Reviewing and consulting on precedent decisions made in the past of the project or region. Assessing the flora and fauna and obtaining opinions from agricultural engineers for the possibility of unusual difficulties and financial burdens during the post-operation rehabilitation process.

6.3. Hearing that local people have complaints about the exploration or project area, although it is not stated in the report.

Prevention: Identifying commitments made to the public, public institutions or tradesmen by getting in touch with the local people, and considering the burden that will come from resolving the issues complained about.

Before the project starts, obtaining opinions from local legal experts regarding the determination of possible violations of customs, traditions and legal norms or the delays that will occur in the implementation of the project.

6.4. Not mentioning the social facilities in the business or camp, as well as the sensitivity of the local people regarding labor force and work safety.

Prevention: The actions of the work safety, human resources and public relations personnel should be questioned, and the camps provided to the personnel, such as locker rooms, dormitories and social facilities, should be visited. In addition, the tendency of the local people to crime and vandalism should be questioned.

7. Conclusion

Although it is not expected for the board of investors or managers to be familiar with the technical details explained, even having superficial knowledge will be of great benefit in the decision-making phase. This guide stays as a “checklist” for any professionals in mining sector. With this article;

- If you are new to the sector, you will learn how technical knowledge weaknesses leave investments vulnerable to fraud,

- If you are experienced in the sector, how the report on your desk should be evaluated,

- The importance of in-company reporting and recording culture even if there is no need to submit it anywhere,

- What the other party may pay attention to in the sale of a license or project,

- How professionals working in the mining sector should work in terms of standards and ethics,

- In fact, we have understood how business should be conducted in such a proper mining company.

Remember, the resources you will spend to know the value of the asset (license) in your case or to know better what you want to buy will protect your investment from great burdens.

Subjects discussed in this article may overlap with your mineral exploration, modeling, mining operation and business development issues and may provide solutions for those. However, remember that various factors specific to your business may bring about different challenges. Therefore, seek support from expert consultants to evaluate all data together in order to convert potential into profit most efficiently.

Should you have any questions regarding the articles or consulting services, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us.

GMRTC Mineral Exploration & Modeling & Operation Consultancy

Istanbul - Izmir - TÜRKİYE

SITE MAP

CONTACT US

Before quoting or copying from our site, you can contact info@gmrtc.com

All elements (texts, comments, videos, images) on the GMRTC website (www.gmrtc.com) are the property of GMRTC unless otherwise stated, and are published to provide insights to interested investors, professionals, and students. Any detail that may arise during your process will affect the subject matter you are interested in on this website; therefore, GMRTC (www.gmrtc.com) is not liable for any damages incurred. It is recommended that you consult experts with all your data before making any decisions based on the information provided.